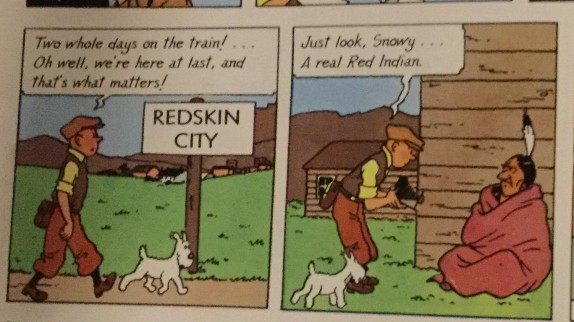

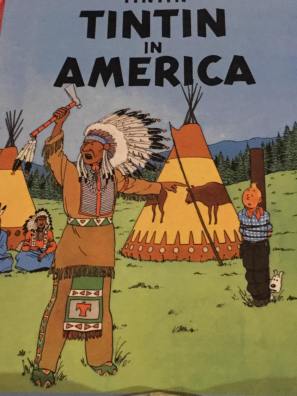

Tintin comics are both a symbol of colonialism and a pastime of francophone culture. The casual racism and stereotyping of cartoons, especially those produced in World War II—as active or passive propaganda—combined patriotic xenophobia with old-school whitewashing of colonial occupations as boy’s adventure stories. Hergé was very much of his time on this matter, as a cursory glance through Tintin in the Congo demonstrates. There was an easy morality to be found within comic books, one which placed the west (specifically, the white west of capital) in the dominant position. The boy reporter has come to the United States and made his way from Chicago to an Indian reservation. The Blackfoot tribe is tricked by a gangster into believing that Tintin is here to take their land. Chaos and violence ensue.

At the end of page 28, Tintin discovers oil and is liberated from the underground cavern he has been trapped in with his dog, Snowy, by the jet of black flood. Within moments, in panel 2 of 11 on page 29, a businessman approaches with lit cigar, contract and pen in hand. “Ok, son! Here’s the contract. Sign there! Five thousand dollars for your oil well…” The boy’s face is away from the reader. Cartoon punctuation of emotional states fills in the picture. Snowy is bewildered. Asked how he knew oil was found less than ten minutes after it blew, the businessman responds, “Unerring American know-how! Never fails!”

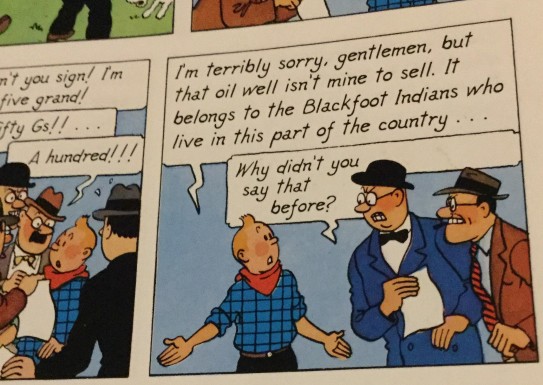

As with insects, where one businessman is, soon there will be others. Suited and ink-wielding, they swarm the boy reporter, going upwards of $100,000.00 for the land. Tintin grows anxious. “I’m terribly sorry, gentlemen, but that oil well isn’t mine to sell. It belongs to the Blackfoot Indians who live in this part of the country…” The businessmen change tracks. “Why didn’t you say that before?”

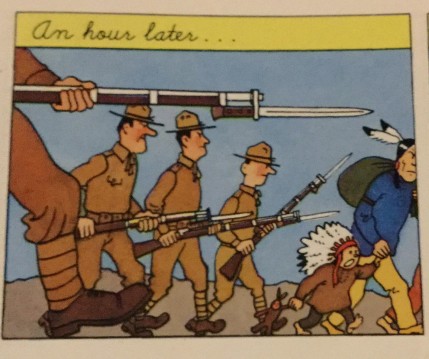

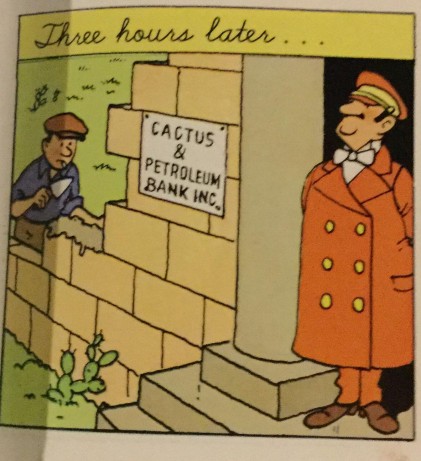

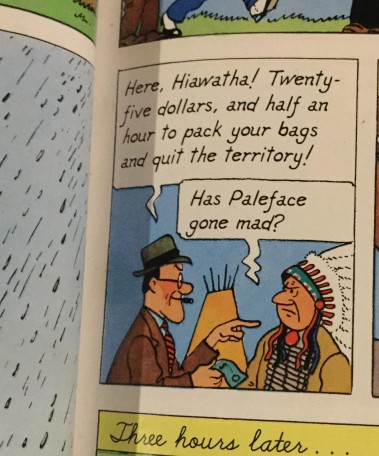

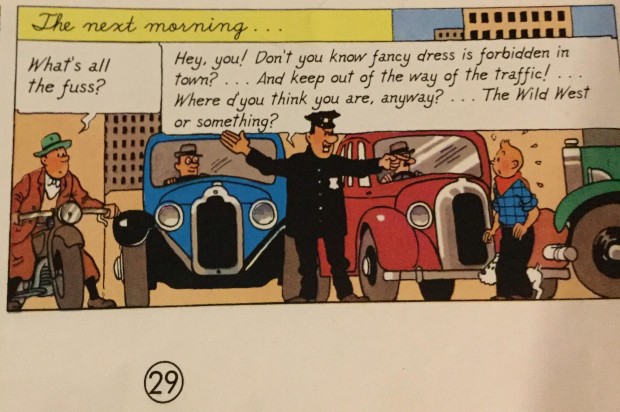

Panel 7 begins the half-page sweep that leaves me turning this comic book over in my mind. The first businessman stands alone, cigar in mouth but apparently unlit now. “Here, Hiawatha! Twenty-five dollars and half an hour to pack your bags and quit the territory!” The left hand points and the right hand holds out a bill. The contract is out of the equation. Looking closely at the bill, it has no value written on it, reading instead as a dollar sign ($) and a large zero (0). The money in hand has no value attributed to it; nor is there any notice that this tender is legal, for all debts, public and private. “Has Paleface gone mad?” the Chief asks. Panel 8, “An hour later…”, shows American military, armed with bayonets, moving the Indians off the land. “Two hours later…” and construction is underway. Gone are the teepees. A faceless man carries two long planks of wood that covers his head. A man with a hat and glasses gives orders, but his mouth is covered by the planks as well. “Three hours later…” and a bricklayer is building the “Cactus & Petroleum Bank, Inc.” while a doorman stands guard. (I wish to make this very clear: a doorman, in full livery, is standing guard at the entrance to an as-yet-to-be-built bank that presumably does not have money in it yet.) Everything happens with comic book speed, to the point that the final panel on the page, “The next morning…”, shows a town of the early 20th Century, not unlike the town that Tintin had just escaped. Tintin walks into traffic—three cars and a motorcyclist held up by a traffic cop. “Hey, you!” the cop exclaims. “Don’t you know fancy dress is forbidden in town? …And keep out of the way of the traffic!… Where d’you think you are, anyway? …The Wild West or something?” Tintin is still wearing his kerchief, his flannel, and his jeans—an outfit too far behind for the busy metropolis; too early for the hipster crowd.

The schoolboy script across the top, representing the passing of time in neat, cursive letters, reminds me of the yellow letter pads we were taught to write on in elementary school. The content of the images reminds me of the stories we were told in elementary school—always cowboys and military might, adventurously heterosexual, but with a sense of decency, good raw material for the Christian fundamentalists who taught us. I’m certain I’ve read this book before, just as sure as Dick and Jane. I’ve written before about childhood and the way these images frame our approach to subjects outside ourselves. I wince when I take a look at Tintin. And yet.

“Where d’you think you are, anyway? …The Wild West or something?”

“Has Paleface gone mad?”

The text was published as a book in 1945. It is just one of the 24 canonical Tintin adventures that took him around the world, into space, and finally into metaphysics. In Tintin in America, Hergé is both celebrating the legacy of American colonialism that would give us a land like Chicago, while summing up the callousness and craziness needed to make colonialism such a valued pastime. There’s the story of New York—rather what was to become New York—being sold for $25. There’s a legacy of military intervention and forced departure from lands—lands that the indigenous people had been forced to move to a generation before after being forced to depart other lands. There is the re-purposing and redevelopment of land in such a way that you wouldn’t even know that there had been anything else there before. All of this in five out of eleven panels on Page 29.

This is not supposed to be in children’s comics. The reality is that most of the media for children is designed by non-children and as such the representations that spring up are larger. Those who create do not exist in blank space. The history of Hergé and the books he read find their way into the Tintin landscapes. We believe that the stories of childhood were innocent or at least that the things that make them unfortunate now occurred out of an historical ignorance—one that many of us are not willing to confess to and apologize for. This even carries over, to an extent, into the biography of Hergé himself, now available as a graphic novel. There is a certain poetic symmetry in the cartooner becoming a cartoon.

In the mire of Tintin’s history, I want to find something redemptive. I want to find a moment of insight that maybe suggests that the rest isn’t so bad because I saw this character as a youth. If there is a virtue to this, it is a reminder of how quickly we move on from our history. It reminds those who read it how we selectively remember the past.

2 thoughts on “On Page 29 of “Tintin in America””